A Momentary Lapse of Reason

| A Momentary Lapse of Reason | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Studio album by Pink Floyd | ||||

| Released | 7 September 1987 | |||

| Recorded | October 1986–May 1987 | |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 51:14 | |||

| Label | EMI | |||

| Producer | Bob Ezrin, David Gilmour | |||

| Pink Floyd chronology | ||||

|

||||

| Singles from A Momentary Lapse of Reason | ||||

|

||||

A Momentary Lapse of Reason is the thirteenth studio album by English progressive rock group Pink Floyd. It was released in the UK and US in September 1987. In 1985 guitarist David Gilmour began to assemble a group of musicians to work on his third solo album. At the end of 1986 he changed his mind, and decided that the new material would instead be included in a new Pink Floyd album. Subsequently Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason and keyboardist Richard Wright (who had left the group in 1979) were brought on board for the project. Although for legal reasons Wright could not be re-admitted to the band, he and Mason helped Gilmour craft what would become the first Pink Floyd album since the departure of lyricist and bass guitarist Roger Waters in December 1985.

The album was recorded primarily on Gilmour's converted houseboat, Astoria. Its production was marked by an ongoing legal dispute between Waters and the band as to who owned the rights to Pink Floyd's name, which was not resolved until several months after the album was released. Unlike most of Pink Floyd's studio albums, A Momentary Lapse of Reason has no central theme, and is instead a collection of rock songs written mostly by Gilmour and musician Anthony Moore. Although the album received mixed reviews and was derided by Waters, with the help of an enormously successful world tour it easily out-sold their previous album The Final Cut. A Momentary Lapse of Reason is certified multi-platinum in the US.

Contents |

Background

After the release of their 1983 album The Final Cut (viewed by some to be a de facto Roger Waters solo record),[1][2] the three members of Pink Floyd worked on individual solo projects. In 1984 guitarist David Gilmour expressed some of his feelings about his relationship with bassist Waters on his second solo album, About Face. He finished touring in support of About Face just as Waters began travelling with his new solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking.[3] Although both musicians had enlisted the aid of a range of successful performers, including—in Waters' case—Eric Clapton, each found that for their fans, the lure of a solo name was somewhat less enticing than that of Pink Floyd. Poor ticket sales forced Gilmour to cancel several dates, and critic David Fricke commented that Waters' show was "a petulant echo, a transparent attempt to prove that Roger Waters was Pink Floyd".[4] After a six-month break, Waters returned to the US in March 1985, with a second tour. He did so without the support of CBS Records, who made no secret of the fact that what they really wanted was a new Pink Floyd album. Waters responded by calling the corporation "a Machine".[5]

At that time, certainly, I just thought, I can't really see how we can make the next record or if we can it's a long time in the future, and it'll probably be more for, just because of feeling of some obligation that we ought to do it, rather than for any enthusiasm.

Meanwhile, after drummer Nick Mason attended one of Waters' London performances in 1985, he admitted that he missed touring under the Pink Floyd banner. His visit coincided with the release in August that year of his second solo album Profiles. The album contained the nominal single, "Lie for a Lie", on which Gilmour sang.[7][8] With a shared love of flying, the two were taking flight lessons, and would together later buy a De Havilland Devon aeroplane. Gilmour also busied himself with other collaborations, including a performance for Bryan Ferry at 1985's Live Aid concert. He also co-produced The Dream Academy's self-named début album, The Dream Academy.[9]

Waters had hinted at his future during a 1982 interview for Rolling Stone, in which he mused: "I could work with another drummer and keyboard player very easily, and it's likely that at some point I will", but in December 1985 he announced that he had left the band, and that he believed that Pink Floyd was a "spent force".[10][11] Gilmour saw matters differently; the guitarist refused to allow Pink Floyd to fade into history, and was intent on continuing with the band: "I told him [Waters] before he left, 'If you go, man, we're carrying on. Make no bones about it, we would carry on.'" Waters' warning was stark: "You'll never fucking do it."[12] He had written to EMI and Columbia declaring his intention to leave the group, and had asked them to release him from his contractual obligations. He had also dispensed with the services of Floyd manager Steve O'Rourke, and employed Peter Rudge to manage his affairs.[7] This left Gilmour and Mason (in their view) free to continue with the Pink Floyd name.[13]

In Waters' absence, Gilmour had been recruiting an array of musicians for a new project. Some months previously keyboard player Jon Carin had jammed with Gilmour at his Hookend studio, where he composed the chord progression for what later became "Learning to Fly", and so he was invited onto the team.[14] Gilmour invited Bob Ezrin (co-producer of 1979's The Wall) to work on his new project, to help consolidate what material had been written.[15] The invitation came only a short time after the Canadian had turned down Waters' offer of a role on the development of his new solo album, Radio K.A.O.S., which Ezrin had been unable to do: "... far easier for Dave and I to do our version of a Floyd record."[16] Ezrin arrived in England in the summer of 1986, for what Gilmour later described as "mucking about with a lot of demos".[17] At this stage there was no firm commitment to a new Pink Floyd album, and publicly, Gilmour maintained that the new material might end up on a third solo album. CBS representative Stephen Ralbovsky had different expectations however; in a November 1986 meeting with Gilmour and Ezrin, the guitarist was left in no doubt as to his feelings: "This music doesn't sound a fucking thing like Pink Floyd".[18] Gilmour later admitted that Waters' absence was a problem, and that the new project was difficult without his presence.[19] Gilmour had experimented with various songwriters such as Eric Stewart and Roger McGough, but eventually settled on musician Anthony Moore,[20] who was later credited as co-writer of "Learning to Fly" and "On the Turning Away". The idea of a concept album was ditched, and Gilmour settled instead for the more conventional approach of a track-list of songs not thematically linked.[21] By the end of that year, he had decided to turn the new material into a Pink Floyd project.[6]

Recording

You can't go back ... You have to find a new way of working, of operating and getting on with it. We didn't make this remotely like we've made any other Floyd record. It was different systems, everything.

A Momentary Lapse of Reason, as it would later be named, was recorded in several different studios, chief among them Gilmour's houseboat Astoria. The boat was moored on the Thames, and the river setting (according to Ezrin) eventually "imposed itself" in all the songs.[23] "Working there was just magical, so inspirational; kids sculling down the river, geese flying by ..."[17] Andy Jackson (a colleague of Floyd cohort James Guthrie) was brought in to engineer the recordings. In a series of discontinuous sessions between November 1986 and February 1987,[24] Gilmour's band of musicians worked on new material, which in a marked change from previous Floyd albums was recorded with a 24-track analogue machine, and overdubbed onto a 32-track Mitsubishi digital recorder. This trend of using new technologies was continued with the use of MIDI synchronisation, aided by an Apple Macintosh computer.[18][25]

After agreeing to rework the material that Ralbovsky had found so objectionable, Gilmour employed extra session musicians including Carmine Appice and Jim Keltner. Both drummers, they later replaced Mason on most of the album's songs; Mason was concerned that he was too out of practice to perform on the album, and instead busied himself with its sound effects.[18][26] Some of the album's drum parts were also performed by drum machines.[27] Gilmour was contacted by Wright's new wife, Franka, who asked if Wright could contribute to the new album. Gilmour considered the request; the keyboardist had left the band in 1979, and there were certain legal obstacles to his re-admittance, but after a meeting in Hampstead he was brought back in.[28] Gilmour later admitted in an interview with author Karl Dallas that Wright's presence "would make us stronger legally and musically". He was therefore employed as a paid musician, on a weekly wage of $11,000,[29] but his contributions were minimal. Most of the new keyboard parts had already been recorded, and so from February 1987 he played some background reinforcement on a Hammond organ, and a Fender Rhodes piano, along with several vocal harmonies. The keyboardist also performed a solo in "On the Turning Away", which was discarded, according to Wright "not because they didn't like it ... they just thought it didn't fit."[22] Gilmour later said: "Both Nick and Rick were catatonic in terms of their playing ability at the beginning. Neither of them played on this at all really. In my view, they'd been destroyed by Roger", a comment which clearly angered Mason, who reflected: "I'd deny that I was catatonic. I'd expect that from the opposition, it's less attractive from one's allies. At some point, he made some sort of apology." Mason did, however, concede that Gilmour was nervous about how the album would be perceived.[29]

"Learning to Fly", with its lyrics of "circling sky, Tongue-tied and twisted, just an earthbound misfit, I", was inspired by Gilmour's flying lessons, which occasionally conflicted with his studio duties.[30] The track also contains a recording of Mason's voice, made during takeoff.[31] The band experimented with audio samples, and Ezrin recorded the sound of Gilmour's boatman (Langley Iddens) rowing across the Thames.[17] Iddens' presence at the sessions was made vital when on one occasion, Astoria began to lean over in response to the rapidly rising river, which was pushing the boat against the pier on which it was moored.[26] "Dogs of War", which Gilmour says was about "physical and political mercenaries", was influenced by an accident during recording. A sampler began playing a sample of laughter, which Gilmour thought sounded like a dog's bark.[32] "Terminal Frost" was one of Gilmour's older demos, which for some time he considered adding lyrics to, but eventually decided to leave as an instrumental.[33] Conversely, the lyrics for "Sorrow" were written before the music. The song's opening guitar solo was recorded in the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. A 24-track mobile studio piped Gilmour's Fender through a public address system, which was recorded in surround sound.[34]

.jpg)

Despite the tranquil setting offered by Astoria, the sessions were often interrupted by the escalating row between Waters and Pink Floyd over who had the rights to the Pink Floyd name. O'Rourke, believing that his contract with Waters had been terminated illegally, sued the bassist for £25,000 of back-commission.[17] In a late 1986 board meeting of Pink Floyd Music Ltd (since 1973, Pink Floyd's clearing house for all financial transactions), Waters learnt that a new bank account had been opened to deal exclusively with all monies related to "the new Pink Floyd project".[35] He immediately applied to the High Court to prevent the Pink Floyd name from ever being used again,[7] but his lawyers discovered that the partnership had never been formally confirmed. Waters returned to the High Court in an attempt to gain a veto over further use of the band's name. Gilmour's team responded by issuing a non-confrontational press release affirming that Pink Floyd would continue to exist, however the guitarist later told a Sunday Times reporter: "Roger is a dog in the manger and I'm going to fight him, no one else has claimed Pink Floyd was entirely them. Anybody who does is extremely arrogant."[29][36] Waters twice visited Astoria, and with his wife had a meeting in August 1986 with Ezrin (the producer later suggested that he was being "checked out"). As Waters was still a shareholder and director of Pink Floyd music, he was able to block any decisions made by his former band-mates. Recording moved to Mayfair Studios in February 1987, and from February to March—under the terms of an agreement with Ezrin to record close to his home—to A&M Studios in Los Angeles: "It was fantastic because ... the lawyers couldn't call in the middle of recording unless they were calling in the middle of the night."[24][37] The bitterness of the row between Waters and Pink Floyd was covered in a November 1987 issue of Rolling Stone magazine, which became its best-selling issue of that year.[29] The legal disputes were, however, finally resolved by the end of 1987.

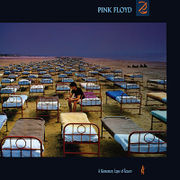

Packaging

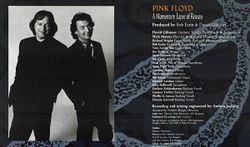

Careful consideration was given to the album's title. The initial three contenders were Signs of Life, Of Promises Broken, and Delusions of Maturity. For the first time since 1977's Animals, designer Storm Thorgerson was employed to work on a Pink Floyd studio album cover. His finished design was a long river of hospital beds arranged on a beach, inspired by a phrase from "Yet Another Movie" and Gilmour's vague hint of a design that included a bed in a Mediterranean house, as well as "vestiges of relationships that have evaporated, leaving only echoes."[38] The cover shows 800 hospital beds, placed on Saunton Sands in Devon (where, coincidentally, some of the scenes for Pink Floyd The Wall were filmed).[39][40] The beds were arranged by Thorgerson's partner, Colin Elgie.[41] A hang glider can be seen in the sky, a clear reference to "Learning to Fly". The photographer, Robert Dowling, won a gold award at the Association of Photographers Awards for the image, which took about two weeks to create.[42] To drive home the message that Waters had left the band, a group photograph, shot by David Bailey, was—for the first time since 1971's Meddle—included in the gatefold. Richard Wright's name appears only on the credit list.[43][44]

Release and reception

A Momentary Lapse of Reason was released in the UK and US on Monday 7 September 1987.[nb 1] It went straight to number three in both countries, held from the top spot by Michael Jackson's Bad, and Whitesnake's 1987. Although Gilmour initially viewed the album as a return to the band's best form, Wright would later disagree, admitting "Roger's criticisms are fair. It's not a band album at all."[43]

The album is noticeably different in style and content to its predecessor, The Final Cut. Gilmour presented A Momentary Lapse as a return to the Floyd of older days, citing his belief that toward the end of Waters' tenure, lyrics were more important than music. Gilmour claimed that "The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here were so successful not just because of Roger's contributions, but also because there was a better balance between the music and the lyrics [than on later albums]". He also stated that with A Momentary Lapse, he had tried to restore the earlier, more successful balance between lyrics and music.[45]

I think it's very facile, but a quite clever forgery ... The songs are poor in general; the lyrics I can't quite believe. Gilmour's lyrics are very third-rate.

Q Magazine's view was that the album was primarily a Gilmour solo effort: "A Momentary Lapse of Reason is Gilmour's album to much the same degree that the previous four under Floyd's name were dominated by Waters",[24] a view echoed by William Ruhlman of Allmusic.com, whose latter-day review refers to A Momentary Lapse as a "Gilmour solo album in all but name".[47] The Toronto Star wrote "Something's missing here. This is, for all its lumbering weight, not a record that challenges and provokes as Pink Floyd should. A Momentary Lapse Of Reason, sorry to say, is mundane, predictable."[48] The Village Voice reviewer Robert Christgau wrote: "In short, you'd hardly know the group's conceptmaster was gone—except that they put out noticeably fewer ideas."[49] Sounds said the album was "back over the wall to where diamonds are crazy, moons have dark sides, and mothers have atom hearts".[50]

A Momentary Lapse of Reason was certified Silver and Gold in the UK on 1 October 1987, and Gold and Platinum in the US on 9 November. It went 2× Platinum on 18 January the following year, 3× Platinum on 10 March 1992, and 4× Platinum on 16 August 2001,[51] easily beating sales of the band's previous album, The Final Cut.[52] The album was reissued in 1988 as a limited edition vinyl album, complete with posters, and a guaranteed ticket application for the upcoming UK leg of the band's UK concerts.[nb 2] The album was digitally remastered and re-released in 1994,[nb 3] and an anniversary edition was released in the US in 1997.[nb 4]

Tour

They threatened me with the fact that we had a contract with CBS Records and that part of the contract could be construed to mean that we had a product commitment with CBS and if we didn't go on producing product, they could a) sue us and b) withhold royalties if we didn't make any more records. So they said, 'that's what the record company are going to do and the rest of the band are going to sue you for all their legal expenses and any loss of earnings because you're the one that's preventing the band from making any more records.' They forced me to resign from the band because, if I hadn't, the financial repercussions would have wiped me out completely.

The decision to tour in support of the album was made before it was even complete, and early rehearsals were chaotic; Mason and Wright were completely out of practice, and realising he'd taken on too much work Gilmour asked Bob Ezrin to take charge. Matters were complicated when Waters contacted several US promoters, and threatened to sue them if they used the Pink Floyd name. Gilmour and Mason funded the start-up costs (Mason, separated from his wife, used his Ferrari 250 GTO as collateral). Some promoters were offended by Waters' threat however, and several months later 60,000 tickets went on sale in Toronto, selling out within hours.[38][40]

As the new line-up (with Wright) toured throughout North America, Waters' Radio K.A.O.S. tour was, on occasion, close by. The bassist had forbidden any members of Pink Floyd from attending his concerts,[nb 5] which were generally in smaller venues than those housing his former band's performances. Waters also issued a writ for copyright fees for the band's use of the flying pig, and Pink Floyd responded by attaching a huge set of male genitalia to the balloon's underside to distinguish it from Waters' design. By November 1987 however, the bassist appeared to admit defeat, and on 23 December a legal settlement was finally reached at a meeting on Astoria.[21] Mason and Gilmour were allowed use of the Pink Floyd name in perpetuity, and Waters would be granted, amongst other things, rights to The Wall. The bickering continued, however, with Waters issuing the occasional slight against his former friends, and Gilmour and Mason responding by making light of Waters' claims that they would fail without him.[56] The Sun printed a story about Waters, who it claimed had paid an artist to create 150 toilet rolls with Gilmour's face on every sheet. Waters later rubbished this story,[57] but it serves to illustrate how deeply divided the two parties had become.[58]

The Momentary Lapse tour was phenomenally successful. In every venue booked in the US it beat box-office records, making it the most successful US tour by any band that year. Tours of Australia, Japan, Europe and the UK soon followed, before the band returned twice to the US. Almost every venue was sold out. A live album, Delicate Sound of Thunder, was released on 22 November 1988, followed in June 1989 by a concert video. A few days later, the album was played by the crew of Soyuz TM-7, making Pink Floyd the first rock band ever to be played in space. The tour eventually came to an end at Knebworth Park in September 1990, after 200 performances, a gross audience of 4.25 million fans, and box-office receipts of more than £60M (not including merchandising).[59]

Track listing

All lead vocals performed by David Gilmour except where noted.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Signs of Life" (instrumental, with spoken vocals by Nick Mason) | Gilmour, Ezrin | 4:24 |

| 2. | "Learning to Fly" | Gilmour, Moore, Ezrin, Carin | 4:53 |

| 3. | "The Dogs of War" | Gilmour, Moore | 6:05 |

| 4. | "One Slip" | Gilmour, Manzanera | 5:10 |

| 5. | "On the Turning Away" | Gilmour, Moore | 5:42 |

| 6. | "Yet Another Movie / Round and Around" (instrumental) | Gilmour, Leonard / Gilmour | 7:28 |

| 7. | "A New Machine (Part 1)" | Gilmour | 1:46 |

| 8. | "Terminal Frost" (instrumental) | Gilmour | 6:17 |

| 9. | "A New Machine (Part 2)" | Gilmour | 0:38 |

| 10. | "Sorrow" | Gilmour | 8:46 |

|

Total length:

|

51:14 | ||

Personnel

|

|

Chart positions

|

|

References

- Notes

- ↑ UK EMI EMD 1003 (vinyl album), EMI CDP 7480682 (CD album). US Columbia OC 40599 (vinyl album released 8 September 1987), Columbia CK 40599 (CD album)[44]

- ↑ UK EMI EMDS 1003[53]

- ↑ UK EMI CD EMD 1003[53]

- ↑ US Columbia CK 68518[53]

- ↑ Mason (2005) states that "rumour had it we would not be allowed in"[55]

- Footnotes

- ↑ Watkinson & Anderson 2001, p. 133

- ↑ Mabbett 1995, p. 89

- ↑ Blake 2008, pp. 302–309

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, pp. 249–250

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, pp. 256–257

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 (Radio broadcast) In the Studio with Redbeard, A Momentary Lapse of Reason, Barbarosa Ltd. Productions, 2007

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Blake 2008, pp. 311–313

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 257

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, pp. 258–260

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, pp. 262–263

- ↑ Jones, Peter (1986-11-22), It's the Final Cut: Pink Floyd to Split Officially, Billboard, p. 70, http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9SQEAAAAMBAJ, retrieved 2009-09-22

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 245

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 263

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 316

- ↑ Blake 2008, pp. 315, 317

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, pp. 267–268

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Blake 2008, p. 318

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Schaffner 1991, pp. 268–269

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 320

- ↑ Mason 2005, pp. 284–285

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Povey 2007, p. 241

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Schaffner 1991, p. 269

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 268

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Povey 2007, p. 246

- ↑ Mason 2005, pp. 284–286

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Mason 2005, p. 287

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 319

- ↑ Blake 2008, pp. 316–317

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Manning 2006, p. 134

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 267

- ↑ MacDonald 1997, p. 229

- ↑ MacDonald 1997, p. 204

- ↑ MacDonald 1997, p. 272

- ↑ MacDonald 1997, p. 268

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 270

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 271

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 321

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Blake 2008, p. 322

- ↑ Mason 2005, p. 290

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Povey 2007, p. 243

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 273

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 323

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Blake 2008, pp. 326–327

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Povey 2007, p. 349

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 274

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 328

- ↑ Ruhlmann, William, A Momentary Lapse of Reason, allmusic.com, http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=10:g9fuxqr5ldje, retrieved 2010-01-24

- ↑ Quill, Greg (1987-09-11) (Registration required), Has Pink Floyd changed its color to puce?, Toronto Star, hosted at infoweb.newsbank.com, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/InfoWeb?p_product=AWNB&p_theme=aggregated5&p_action=doc&p_docid=10B9DDB1180E5340&p_docnum=36&p_queryname=3, retrieved 2010-01-24

- ↑ Christgau, Robert, A Momentary Lapse of Reason, robertchristgau.com, http://www.robertchristgau.com/get_album.php?id=5686, retrieved 2010-01-24

- ↑ Manning 2006, p. 136

- ↑ Povey 2007, pp. 349–350

- ↑ Povey 2007, p. 230

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 Povey 2007, p. 350

- ↑ Povey 2007, p. 240

- ↑ Mason 2005, p. 300

- ↑ Blake 2008, pp. 329–335

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 353

- ↑ Schaffner 1991, p. 276

- ↑ Povey 2007, pp. 243–244

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse Of Reason (Album), ultratop.be, http://www.ultratop.be/en/showitem.asp?interpret=Pink+Floyd&titel=A+Momentary+Lapse+Of+Reason&cat=a, retrieved 2010-01-25

- Bibliography

- Blake, Mark (2008), Comfortably Numb—The Inside Story of Pink Floyd (Paperback ed.), Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, ISBN 0306817527

- Mabbett, Andy (1995), The Complete Guide to the Music of Pink Floyd, Omnibus Pr, ISBN 071194301X

- MacDonald, Bruno (1997), Pink Floyd: Through the Eyes of the Band, Its Fans, Friends and Foes (Paperback ed.), Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, ISBN 0306807807

- Manning, Toby (2006), The Rough Guide to Pink Floyd (First ed.), London: Rough Guides, ISBN 1843535750

- Mason, Nick (2005), Philip Dodd, ed., Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (Paperback ed.), London: Phoenix, ISBN 0753819066

- Povey, Glenn (2007), Echoes, Bovingdon: Mind Head Publishing, ISBN 0955462401, http://books.google.com/books?id=qnnl3FnO-B4C

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1991), Saucerful of Secrets (First ed.), London: Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN 0283061278

- Watkinson, Mike; Anderson, Pete (2001), Crazy Diamond: Syd Barrett & the Dawn of Pink Floyd (Illustrated ed.), Omnibus Press, ISBN 0711988358, http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=kPJlLjf4OogC

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||